Understanding Obsolete Currency

Obsolete currency refers to forms of money that have lost their status as a medium of exchange, store of value, or unit of account within a society. Unlike current forms of currency, which are widely accepted for transactions and hold value over time, obsolete currencies may have once served these purposes but are now deemed ineffective, often becoming mere artifacts of historical significance. The evolution of currency can be traced back to barter systems, where goods and services were exchanged directly. Over time, societies moved towards standardized forms of currency, such as coins and paper money, which facilitated commerce.

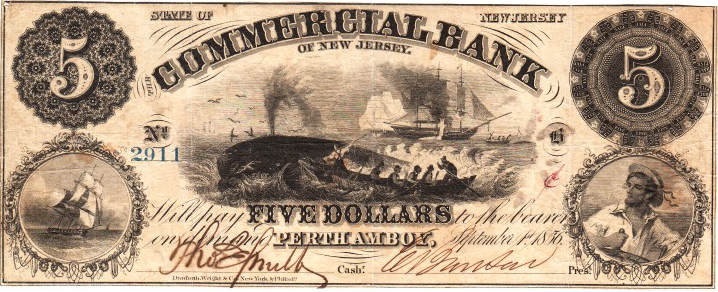

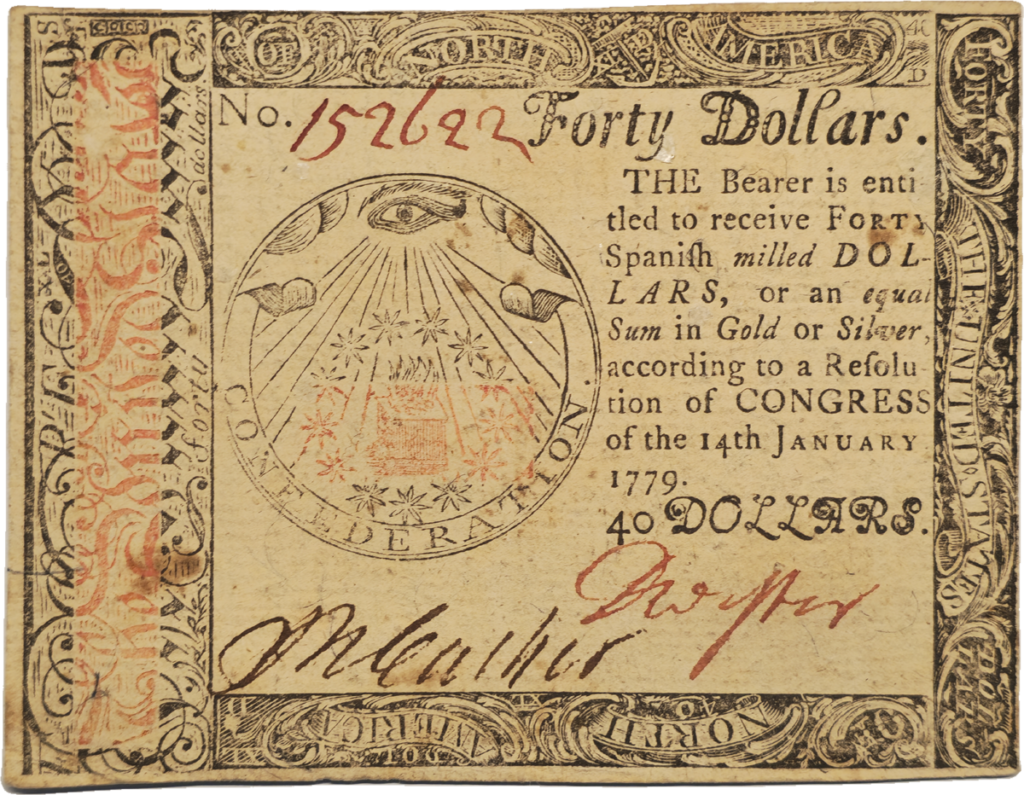

The United States made its first national paper currency in 1862(top) making private bank notes obsolete. This was in response to, and to pay for the civil war as the Southern States created the Confederacy and their own paper currency(bottom).

The reasons currencies become obsolete are manifold. Economic factors such as hyperinflation, political instability, or advances in technology can render a currency ineffective. For instance, the transition from silver-backed currency to fiat money in the 20th century marked a significant shift in the banking system. Fiat money, which relies on government decree rather than intrinsic value, became the standard. In other words, it is based on a promise. Consequently, currencies that no longer met the needs or trust of the public were gradually phased out. This demonstrates how the banking system directly influences currency’s relevance.

Historically, the obsolescence of currency serves as a reflection of economic and societal shifts. For instance, currencies like the German Papiermark became obsolete after World War I due to hyperinflation. And more recent digital currencies challenge conventional notions of currency altogether. Understanding the importance of this obsolescence provides context for economic history. It illustrates how public confidence in a currency, regulated by the banking system, can determine its lifespan. The examination of obsolete currency not only highlights the past practices that shaped economic structures but also emphasizes the ongoing evolution of money itself.

The Role of Banks in Currency Creation

The evolution of currency is heavily influenced by the banking system, which plays a crucial role in both its creation and dissolution. Central banks are pivotal institutions in this process, as they are typically tasked with issuing national currency. When a central bank decides to issue a new currency, it often reflects an underlying economic policy aimed at stabilizing or stimulating the economy. This issuance is regulated by specific mandates designed to ensure credibility and trust among the populace. The value of currency is, thus, intrinsically linked to the actions of these institutions, which manage interest rates, inflation, and public confidence.

Regulatory frameworks established by banking institutions dictate not just the volume of money supply but also the stability of that supply. Poor regulatory practices can lead to the creation of less stable currencies, which can subsequently become obsolete. For example, hyperinflation in certain historical contexts, such as in the Weimar Republic in the early 20th century or Zimbabwe in the late 2000s, showcases how banks’ mismanagement and inadequate policies contribute to a currency’s erosion of value, leading to its eventual collapse.

Additionally, the dissolution of currencies can often be traced back to banking decisions that undermine trust. When banks engage in practices that create uncertainty—whether through excessive lending, lack of transparency, or failure to adopt adequate safeguards—the resulting loss of confidence in the monetary system can lead citizens to abandon that currency. The case of the Continental Currency during the American Revolutionary War serves as a historical example, where excessive issuance without sufficient backing led to rapid depreciation, ultimately causing it to fall out of favor.

Bills authorized by the congress after the revolutionary war were known as ‘Continentals’. Inflation and lack of trust in this currency spawned the derogatory saying; “Not worth a Continental”

This interplay between banking policies and currency stability highlights the banking system’s powerful role in shaping the life cycle of currencies. Its influence extends far beyond mere issuance; it includes the critical attributes of value retention and public perception. Thus, understanding this relationship is essential to grasping how currencies may fall into obsolescence over time.

Key Historical Examples of Obsolete Currencies

The evolution of currency has seen numerous instances where certain forms of money have become obsolete, often due to economic turmoil, hyperinflation, or a loss of public trust in the banking system. One notable example is the German Papiermark, which became the official currency of Germany post-World War I. The Weimar Republic experienced severe hyperinflation in the early 1920s, where the value of the Papiermark plummeted due to excessive printing of money to cover war reparations and economic instability. As a result, prices soared, and everyday citizens found themselves carrying stacks of banknotes for basic necessities. Ultimately, the Papiermark was replaced by the Rentenmark in 1923 as a measure to restore confidence in the banking system.

Another significant case is the Soviet Ruble, which underwent multiple changes throughout its existence. The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 led to economic chaos, rampant inflation, and the decline of the Ruble’s value. By the mid-1990s, the government struggled to maintain control over inflation, leading to the introduction of a new Ruble design in 1993 as a means to stabilize the economy. This currency transition was a direct response to the loss of confidence in the prior system, demonstrating how socio-economic factors can lead to the obsolescence of a currency.

In more recent history, the Zimbabwean Dollar serves as a stark example of hyperinflation that rendered a currency virtually worthless. From the late 1990s to the late 2000s, Zimbabwe faced severe economic challenges, significantly increasing the money supply without real backing. By November 2008, inflation reached an astronomical 89.7 sextillion percent, leading to the abandonment of the Zimbabwean Dollar in favor of foreign currencies, including the US Dollar and the South African Rand. These historical examples illustrate the precarious nature of currency and how fragile public trust can be, highlighting the pivotal role of the banking system in maintaining economic stability.

Lessons Learned and Future Implications

The examination of obsolete currencies offers vital insights into the evolution of financial systems and banking practices. One significant lesson is the understanding of trust as a cornerstone of any currency’s value. Historical cases of currency collapse typically stemmed from loss of public confidence due to volatile economic conditions, mismanagement, or inflation. Modern financial institutions must heed these lessons to maintain stability in current banking systems, particularly as the world witnesses a rapid shift toward digital currencies.

The rise of cryptocurrencies has transformed the conversation around money, highlighting alternative methods of transaction and storage of value. As decentralized finance becomes more prevalent, traditional banking models may need to adapt to accommodate new technological advancements. The integration of blockchain technology presents opportunities for transparency and security; yet, it raises questions regarding regulation and consumer protection. Policymakers are tasked with establishing frameworks that foster innovation while mitigating potential risks associated with unregulated markets.

Physical investments

Furthermore, the implications for regulatory policies are profound. Governments and regulatory bodies must act decisively to assure their citizens that national digital currencies remain secure and stable. Learning from past failures of currencies, it becomes imperative to cultivate a robust regulatory environment that upholds public trust. This involves transparency in monetary policies and clear communication about digital currencies’ functionality and risks.

Looking ahead, the future of money is likely to be characterized by hybrid systems that merge traditional banking and digital assets. The lessons gleaned from obsolete currencies encourage an agile approach to evolving monetary practices. The ongoing challenges will necessitate continuous learning, adaptation, and evolution within the banking system to ensure resilience against the pitfalls experienced by previous financial frameworks.